Originally published in New York Times

Governments are committing to net zero. Sustainable products are being sold to you on Instagram. Banks are pushing E.S.G.s. As climate change gets worse, it seems like everyone wants you to know that they’re doing something about it. But what do those words mean? Are they really communicating information — or obfuscating?

There’s a long history of choosing words that are meant to advance an agenda. Two decades ago, a pollster named Frank Luntz famously advised Republicans to say “climate change” instead of “global warming,” a phrase that sounded less alarming, to try to stave off calls for urgent action.

A lot has changed since then, but what hasn’t is the power of words to shape the way people think about climate risks.

As government and business leaders gather in Glasgow, The New York Times climate team has compiled a list of jargon you’re likely to hear, along with definitions, context and caveats. Terms like carbon pricing and carbon tax, renewable versus clean energy, and natural gas versus fracked gas. Think of it as a user’s guide for the climate debate — one in which the science is clear, yet the language is anything but.

NET ZERO

When a country or company promises to “get to net zero” — make sure you read the fine print.

﹏

Scientists have warned that global warming will keep getting worse until humanity reaches “net zero” emissions globally — that is, the point at which we are no longer pumping any additional greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. So, in recent years, a growing number of countries and businesses have been making their own pledges to “go net zero” by various dates. The United States and China both have net-zero promises. So do Amazon and Apple.

In theory, net zero is a sound idea. In practice, the concept can easily be abused.

When governments or companies pledge to go net zero, they’re not always promising to stop emitting carbon dioxide altogether. Often they’re saying that they will reduce fossil-fuel emissions from their own factories, homes and cars as much as they can and then offset whatever they can’t get rid of through other means, such as by planting trees or using technology to pull carbon dioxide out of the air.

Those offsets can be contentious. Trees can absorb carbon, but they can also burn in wildfires. Carbon removal technology is still in its infancy. Critics worry that leaders and businesses may be using the uncertain promise of such offsets to avoid making deeper cuts today.

At the same time, many countries’ net zero pledges are vague and not yet backed by concrete policies to curb emissions. That’s true of both the United States and China. Many corporate net zero pledges have asterisks: Some companies have pledged to clean up their offices, for instance, but not their broader supply chains. It’s possible to set a rigorous net-zero target, but these promises usually need plenty of scrutiny.

— Brad Plumer

SUSTAINABILITY

Getting there is harder than marketers would have you believe.

﹏

Claims of sustainability are ubiquitous. A quick online search offers up a vast selection of products branded as such, including a “Sustainability On-The-Go Gift Box,” complete with wooden utensils and a tumbler wrapped in bamboo; a T-shirt emblazoned with the words “Sustainable AF”; and a toilet paper stand that encourages users to use less by dispensing one sheet at a time. In many cases, it’s not even clear what a company is claiming. Without independent verification, the term is meaningless. Worse, it can backfire, as in the case of cotton tote bags. If we’re serious about sustainability, what about reducing consumption?

And it’s not just about consumer goods. Pick your industry — airlines, restaurants, banking, fossil fuel companies, you name it — and you’ll find companies marketing sustainability, often with little to back it up.

But what if we did it right?

The United Nations defines sustainability as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.”

That kind of true sustainability means bringing humans into balance with the planet and its resources. It requires transformative changes in how we live. But if we can do the hard work to get there, we will do nothing less than save our world.

— Catrin Einhorn

CARBON FOOTPRINT

Useful concept or industry ploy?

﹏

Say you decide to have a nice steak dinner. You might know that cows belch gas into the atmosphere, which helps make cattle a sizable source of greenhouse gas emissions. But that isn’t all: glasses of California wine, bottled water for the table and cheesecake for dessert all generated emissions when they were produced and again when they traveled to your table. The amount adds up to your dinner’s “carbon footprint.”

The tally of emissions related to everything else in your life — heating your home, driving to and from work, even the pet food your cat or dog eats — is your household’s carbon footprint or its contribution to global warming.

Researchers developed the idea of a carbon footprint in the 1990s as a legitimate sustainability research tool. (It wasn’t invented by the oil giant BP as some have suggested.) But critics say the fossil fuel industry has co-opted the idea to focus attention on individual actions and responsibility, rather than on the wider structural changes needed to rein in emissions, including a much faster shift toward clean or renewable energy.

A carbon footprint is still a useful concept, though. It allows us to see that the carbon footprint of a typical American is many times that of a resident of the Global South. We can talk about the carbon footprint of companies, industries or even entire nations. And yes, individual actions do matter: Frequent flying, for example, comes with a huge carbon footprint. It would help to tread more gently.

— Hiroko Tabuchi

MITIGATION

Climate mitigation is different from disaster mitigation.

﹏

This is a term used by both climate scientists and disaster experts, but for completely different scenarios.

In the context of climate change, mitigation refers to anything that reduces emissions of planet-warming gases. Think of the shift from coal-fired electricity generation to wind and solar, from gas powered cars to electric, or toward more energy efficient appliances. Without significant progress on mitigation, and quickly, the planet faces catastrophe.

Mitigation means something else entirely among emergency managers and other disaster experts, who use it to talk about protecting people against the effects of storms, wildfires or other hazards. Confusingly, this is what climate experts sometimes refer to as “adaptation.” (See the next entry to unravel that.) One way to know if that’s the sort of mitigation being discussed is to listen for the more precise phrases disaster mitigation or hazard mitigation.

— Christopher Flavelle

ADAPTATION

It’s not the same as resilience.

﹏

Adaptation is the counterpart to mitigation. It refers to steps aimed at blunting the current consequences of climate change, and preparing for what happens as they get worse. Some good examples are changing how and where we build houses and roads, helping people move away from places vulnerable to flooding or wildfires, or planting different kinds of crops as weather patterns change.

This term is sometimes used interchangeably with resilience, but the terms have important differences. Resilience means maintaining a way of life, but with better protection; adaptation means changing a way of life that is becoming too hard to sustain. Think of protecting a beach town from hurricanes with a seawall (resilience), versus helping people move somewhere else (adaptation).

Adaptation used to be a dirty word among environmentalists, who viewed the notion as defeatist — an admission of the failure to cut emissions, or an invitation not to try. As the effects of climate change get worse, that criticism has faded. The need to adapt, while still trying to cut emissions, has become indisputable. But the term still carries an element of euphemism, especially because poorer communities and nations have far less ability to adapt than wealthier groups do.

— Christopher Flavelle

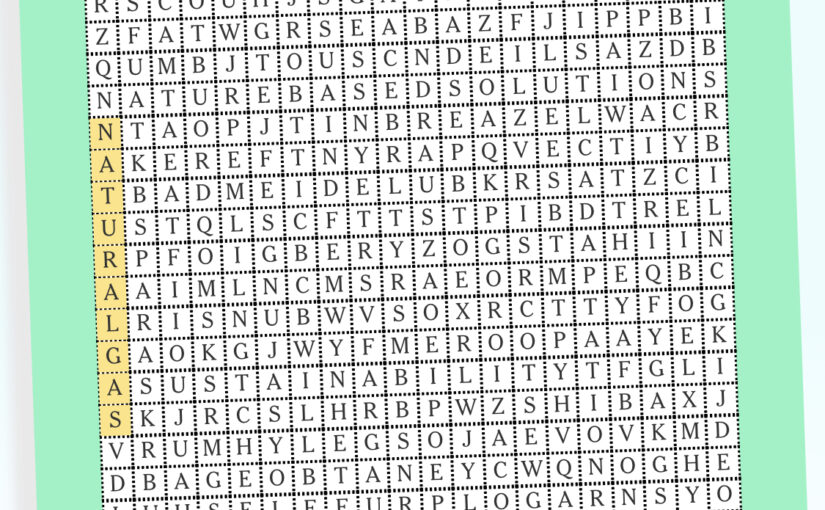

NATURE-BASED SOLUTIONS

They can help a lot, but not as an excuse to burn fossil fuels.

﹏

Nature-based solutions use nature to help solve human problems, often climate-related ones. For example, peatlands, seagrass meadows and forests act as carbon sinks, keeping greenhouse gases out of the air. In cities and towns, trees cool people during heat waves. Mangroves and coral reefs protect coasts from storms. In these ways and others, nature-based solutions can both help fight climate change and guard against its consequences, while also nurturing the world’s biodiversity. They are a critical tool.

But some companies are looking to them as a way to achieve net-zero emissions without substantive cuts in fossil fuel use. The science is clear: Nature can’t store enough greenhouse gases to let us keep spewing them into the atmosphere at anywhere near current rates. Moreover, nature-based solutions are themselves threatened by climate change. Forests are burning in more intense wildfires. Coral reefs are dying from warmer, acidified waters. When ecosystems succumb, they go from storing greenhouse gases to emitting them. So unless nature-based solutions are combined with drastic reductions in fossil fuel emissions, they are hijacked into greenwashing.

The ultimate nature-based solution for climate change? Leave fossil fuels in the ground.

— Catrin Einhorn

CARBON CAPTURE

Plus, its cousin, carbon removal.

﹏

The simplest way to keep carbon out of the atmosphere is to not put it there in the first place. But since the burning of fossil fuels remains widespread, engineers are also exploring strategies to capture or remove the resulting carbon dioxide after the fact. There are two broad ideas here, though both have plenty of question marks.

Carbon capture generally refers to technology that can trap carbon dioxide coming out of the smokestack of a factory or power plant before it can escape into the atmosphere and warm the planet. The captured carbon dioxide is then either buried underground permanently, turned into a useful product like concrete, or, more contentiously, used to pull out more oil from the ground. Some early plants do exist today, although the technology has struggled to become widespread, in part because of the high costs involved.

Carbon removal is slightly different and generally refers to pulling carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere long after it was released. Trees can do this naturally, of course, and planting forests can be a form of carbon removal, although there’s only so much land to go around. But some companies are experimenting with technological carbon removal like direct-air capture — basically, giant fans that suck carbon out of the sky and inject it underground.

Carbon removal tech is even less well developed than carbon capture and usually far more expensive, though scientists say it may be necessary if we want to reach net-zero emissions or if we want to draw down carbon from the atmosphere in order to reverse some of the global warming we’ve already caused.

— Brad Plumer

GEOENGINEERING

Also known as climate intervention — depending on whom you ask.

﹏

Carbon removal is sometimes called geoengineering — deliberately intervening in the composition of the atmosphere. But geoengineering is also used to describe something entirely different from carbon removal: Injecting aerosols into the stratosphere to reflect more of the sun’s energy back into space (sometimes called solar geoengineering or solar radiation modification), which scientists say could quickly and cheaply but temporarily reduce global temperatures, as a sort of stopgap measure until the world can cut emissions.

The concept is wildly controversial. Even if such a scheme worked, nobody is surewhat the effect would be on different parts of the world. Some regions could see devastating reductions in rainfall or other changes to weather patterns. And even conducting basic research into solar geoengineering is viewed by many as a moral hazard, creating the risk that society will conclude (mistakenly) that cutting greenhouse gas emissions is no longer necessary, and so stop pursuing more costly and challenging steps to reduce those emissions.

The backlash has been so intense that some advocates for geoengineering research have started referring to it as climate intervention. Whatever term gets used, the debate over whether and how to block the sun’s rays will only intensify as the effects of climate change increase and the world starts to run out of time for better options.

— Christopher Flavelle

ELECTRIC

E.V.s, H.E.V.s, P.H.E.V.s and F.C.V.s. Phew!

﹏

A car dealership of the future might sell an array of vehicles with confusing acronyms. What do they mean, what are the chances you’ll actually drive one and what does it mean for emissions?

Let’s start with H.E.V.s, sometimes just called H.V.s. There’s a chance you know someone who drives an H.E.V., or hybrid electric vehicle or even own one yourself: Toyota debuted the first gas-electric hybrid, the Prius, in 1997. The technology revolutionized the auto industry with an electric-motor-assisted gasoline engine that greatly cut down on the amount of gas the car needed.

A P.H.E.V., or plug-in hybrid vehicle, is simply an extension of that technology. A P.H.E.V. can generally run on just its battery, which can be plugged into a charging station. But like the Prius, a gasoline engine can and does kick in. (In a regular hybrid, the batteries are charged via regenerative braking — which takes the energy generated when you slow or stop your car, and stores it — or from the gasoline engine itself.)

An E.V., or electric vehicle, runs solely on batteries that power an electric motor. So, no internal combustion engine, no fuel tank, no exhaust pipe. Multiple studies have found that E.V.s — sometimes called B.E.V.s, for battery-electric vehicle — generally have the smallest emissions of all currently available technologies, though a lot depends on the local power grid. (There are also other environmental impacts to consider.)

F.C.V.s, or fuel-cell vehicles, are powered by hydrogen rather than a battery and also produce no tailpipe emissions other than water vapor and air. But hydrogen is currently produced mainly from natural gas, a fossil fuel, and piping hydrogen everywhere would require significant new investments in hydrogen infrastructure, alongside our growing E.V. charging infrastructure. That raises questions about both the climate-friendliness, and practicality, of F.C.V.s.

— Hiroko Tabuchi

CLEAN ENERGY

Not to be confused with renewable energy.

﹏

People generally use “clean energy” to refer to any source of energy that doesn’t add significant greenhouse gases to the atmosphere, usually in contrast to fossil fuels like coal, gas and oil. But what counts as clean can be highly contentious. And it’s not always the same as renewable energy.

Wind and solar power are broadly considered clean, although the manufacturing of wind turbines and solar panels can add a (relatively small) bit of carbon to the air upfront. They’re also considered renewable, since wind and sunlight aren’t expected to run out anytime soon.

Not all renewables are necessarily clean, though. For instance, bioenergy, the burning of wood or other plants for electricity or fuel, can be renewable. But, if handled poorly, it can create a fair amount of emissions.

Nuclear power plants are often considered clean, since they don’t release any carbon dioxide once they are built and generating electricity. But not everyone agrees with this characterization because of the radioactive waste left over. And nuclear plants aren’t considered renewable, since fuel supplies are large but not infinite.

More controversially, industry groups will sometimes refer to natural gas as clean, since it produces less carbon dioxide and far fewer air pollutants than coal does when burned. But natural gas still produces far more carbon than wind, solar or nuclear power, and its use can lead to leaks of methane, a potent greenhouse gas in its own right.

— Brad Plumer

NATURAL GAS

What’s so natural about it?

﹏

That’s a question some environmental groups have started to ask about the gas that powers and heats our homes, but is also a fossil fuel — and fossil fuels are the main drivers of human-caused climate change.

Technically, natural gas does occur naturally, and is drilled out of the ground alongside oil. But in the United States, companies often “frack” for gas, which involves injecting a mixture of water, sand and chemicals at high pressure into the rock. That process is hardly natural, critics say, and some have started to call natural gas “fracked gas” or “fossil gas” to make this point.

That isn’t the only debate swirling around gas. Because gas burns cleaner than coal or oil, industry has long referred to it as a “bridge fuel” between coal and renewable energy. But scientific research has started to show how drilling for gas releases large amounts of methane, a potent greenhouse gas, into the atmosphere. Those emissions play a big role in warming the planet, especially in the shorter term.

Scientists now say the world shouldn’t be investing in new pipelines and other gas infrastructure that locks nations into using gas for decades to come. And a growing chorus of critics suggest yet another name for natural gas: methane gas. Anything, they say, but “natural.”

— Hiroko Tabuchi

E.S.G.

Darling of the financial world.

﹏

You might have heard this acronym in relation to your retirement or mutual funds, if you have them. Investing in profitable companies that are also trying to adopt better practices, or at least not making a negative impact, is becoming increasingly popular.

Between 2018 and 2020, American investments in E.S.G. companies (the letters stand for environmental, social and governance) grew by 42 percent to $17 trillion. Today, more than a third of all the investment assets in the United States fall under this broad category of sustainable and responsible investing. But what kind of company qualifies for this designation?

Much like with the term sustainability, there is little agreement over what E.S.G. actually means. There is also considerable debate over whether a company should have to abide by all three principles. For instance, what if an equipment company puts its workers first but supplies to the fossil fuel industry? Or what if a renewable energy company has poor labor practices? Should both companies be entitled to carry the label? And should the upstream carbon emissions, or end-of-life effects, of a company’s products be classified, too?

There are agencies that issue E.S.G. ratings, but their metrics may not align with how the general public views social responsibility. Last year, a major tobacco company was recognized as a leading E.S.G. company. So, too, have some of the most recognizable consumer products brands, including a number that have been named among the world’s top plastic polluters. But E.S.G. investing is not the same as impact investing, which focuses on companies whose primary goal is to positively impact society.

In general, E.S.G. investing is one of the forces keeping pressure on companies to prioritize their environmental and social commitments. But critics say it’s time for government regulators to require companies to report the underlying metrics that make up their claims, including diversity data and carbon emissions numbers that are audited by outside regulators.

— Winston Choi-Schagrin

CARBON PRICING

A market-based solution.

﹏

Some economists have long argued that carbon pricing is an elegant way to tackle climate change. Just charge companies and consumers more for the emissions they produce, and people will have ample incentive to burn less oil, coal or gas, and shift to cleaner energy. In practice, of course, it’s complicated.

There are two main ways to do carbon pricing. The simplest is a carbon tax, which is usually just a flat tax levied on oil, gas and coal. Countries like Canada and Sweden have carbon taxes, although in practice these policies sometimes come with exemptions and loopholes. And politicians are often reluctant to set the carbon tax high enough to have a significant effect on behavior, because they fear a backlash from voters.

There’s also a cap-and-trade system, in which a government sets a cap on overall emissions and steadily tightens that cap over time. Large polluters must procure permits for every ton of carbon dioxide they emit, and the number of permits dwindles over time, driving up the price. California and the European Union both have cap-and-trade systems, although it can be tricky to design these programs so that they work well.

Carbon pricing isn’t the only way to do climate policy. Many governments, including states like California, prefer to directly regulate the fuel efficiency of cars and trucks or mandate electric vehicles rather than using carbon prices to make gasoline so expensive that consumers opt for cleaner vehicles on their own. And in the United States, most states have opted to mandate renewable energy directly rather than use carbon pricing to clean up power plants.

— Brad Plumer